The Second Tsunami

Doug Bock Clark

The turtle was crying.

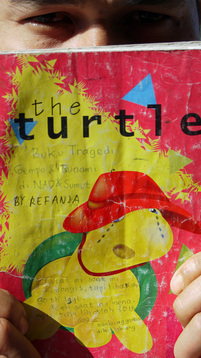

On October 9, 2011, 6 years, 10 months, and 275 days after the tsunami, Rizaldi handed me his dairy of the catastrophe.

His memories were recorded in a typical Indonesian school exercise book decorated with a cartoon turtle on its neon pink cover. The reptile wore a floppy sunhat with a chinstrap and a goofy smile, but when Rizaldi was thirteen, he had drawn tears spilling from its eyes using a blue ballpoint pen. The manufacturer’s title, “The Turtle,” was stamped on the cardboard above the illustration, but long ago he had penned an unofficial name below in Bahasa Indonesian: “The Book of Tragedy, Earthquake and Tsunami, in Aceh and Northern Sumatra.”

“I want it to be like proof that the tsunami actually happened,” Rizaldi said in halting English, “that it existed, that [the outside world] came to help Aceh… Acehnese don’t talk about that time. Even you, you don’t know about that time of the tsunami. I want to share it to America, to Australia, to the world. It is important that they know how we felt.”

The diary was decrepit. Two rusted staples barely held the cardboard covers together. Some of the pages fluttered to the floor as I opened it. When I lifted the fallen paper, I found it soft with years, aged yellow, the ink faded.

On October 9, 2011, 6 years, 10 months, and 275 days after the tsunami, Rizaldi handed me his dairy of the catastrophe.

His memories were recorded in a typical Indonesian school exercise book decorated with a cartoon turtle on its neon pink cover. The reptile wore a floppy sunhat with a chinstrap and a goofy smile, but when Rizaldi was thirteen, he had drawn tears spilling from its eyes using a blue ballpoint pen. The manufacturer’s title, “The Turtle,” was stamped on the cardboard above the illustration, but long ago he had penned an unofficial name below in Bahasa Indonesian: “The Book of Tragedy, Earthquake and Tsunami, in Aceh and Northern Sumatra.”

“I want it to be like proof that the tsunami actually happened,” Rizaldi said in halting English, “that it existed, that [the outside world] came to help Aceh… Acehnese don’t talk about that time. Even you, you don’t know about that time of the tsunami. I want to share it to America, to Australia, to the world. It is important that they know how we felt.”

The diary was decrepit. Two rusted staples barely held the cardboard covers together. Some of the pages fluttered to the floor as I opened it. When I lifted the fallen paper, I found it soft with years, aged yellow, the ink faded.

~

On 8 a.m. Sunday, Dec. 26th, 2004, the Indian Ocean was rocked by a 9.0 magnitude earthquake, the third most powerful ever recorded on seismograph. The northern edge of the India Plate dove 15 meters beneath the Burma Plate. As the India Plate subsided, the Burma Plate shot up, releasing energy that geologists estimate was about 550 million times more powerful than the atomic explosion at Hiroshima, displacing colossal volumes of water. Countries as far away as South Africa, 8,000 km. to the west, were swamped by the resulting tsunami, but the landmass closest to the epicenter was the northern tip of Sumatra Island—Aceh, Indonesia, Rizaldi’s home. There the wave struck with such power that it literally obliterated barrier islands. It deposited a 2,600 ton ship 4 km. from shore.

Ultimately, the tsunami proved to be the deadliest recorded in world history. Of the 225,000 victims, around 170,000 were Acehnese.

Ultimately, the tsunami proved to be the deadliest recorded in world history. Of the 225,000 victims, around 170,000 were Acehnese.

~

The second page of Rizaldi’s diary revealed an introduction. “The terrifying occurrence of the tsunami,” it began in Bahasa Indonesian, “has left behind trauma and sadness. Everything I love and honor has been finished, swept away by the tsunami… Maybe this was all a warning, an answer to our actions, from Allah. Hopefully, the tsunami can make us understand the wisdom of Allah so that we can improve the future.”

~

Before the wave struck Aceh, villagers living near the beach witnessed a miracle: the ocean retreated hundreds of feet, revealing swaths of glistening seabed covered with stranded marine life, from fish to squid. Children, many of whom spend their Sundays playing on the beach, rushed to gather the sudden bounty. Men and women from the villages soon followed. Minutes later, the wave blackened the horizon. It’s almost certain everyone saw the tsunami approaching—when it hit Aceh’s coastline it towered from 30 to 75 feet in height—but because it charged them at 100 miles an hour, no one could flee.

Rizaldi’s village, Emperom, was 4 km. inland. Before reaching Emperom, the wave leveled Lamteh, a coastal fishing village. Photos of the town after the event reveal the only things left standing were the concrete walls of the local mosque. The mosque’s decapitated dome was swept several hundred yards away to the middle of a rice paddy. Of Lamteh’s 9,000 inhabitants, around 1,000 survived, most of whom were lucky enough to have been elsewhere that morning.

Abandoning the husk of Lamteh the wave trampled on, reaching Rizaldi’s home in less than a minute.

Rizaldi’s village, Emperom, was 4 km. inland. Before reaching Emperom, the wave leveled Lamteh, a coastal fishing village. Photos of the town after the event reveal the only things left standing were the concrete walls of the local mosque. The mosque’s decapitated dome was swept several hundred yards away to the middle of a rice paddy. Of Lamteh’s 9,000 inhabitants, around 1,000 survived, most of whom were lucky enough to have been elsewhere that morning.

Abandoning the husk of Lamteh the wave trampled on, reaching Rizaldi’s home in less than a minute.

~

On Dec. 26th, 2004, Rizaldi’s father left the house at 6 a.m., just as dawn was turning the high cirrus clouds pink, to sell vegetables at the traditional market, Pasar Seutui.

When I first met Rizaldi he described himself as being from an “unpretentious background.” Before the tsunami, his father sold produce at the traditional market, his mother tended house, and his brother was studying at a technical high school to become a motorbike mechanic. They lived a simple life, but Rizaldi had great respect for his parents, especially his mother, who taught him extra lessons after school and checked his homework every night.

At the time of the tsunami, Rizaldi had already distinguished himself in Emperom’s middle school and been offered a scholarship to a prestigious private high school in Banda Aceh, the capital city, 15 km. away. However, he had declined the award because his family couldn’t afford the daily bus fare. Still, his parents had decided to enroll him in an academic high school, rather than a technical school like his brother, ambitious that he could win a university scholarship and provide for their old age.

Even as a thirteen-year-old boy, Rizaldi was unsatisfied with anything but perfect marks in school. He understood that it was his responsibility to improve his parents’ lives.

At 7:15 a.m., Rizaldi asked permission from his mother to read the Koran at the balai ngaji. (A balai ngaji is a small informal mosque built in villages without a large enough population to fund a full-sized house of worship.) She wrapped a lunch of rice and salted fish in banana leaves for him. He kissed her hand and scampered outside leaving her, his brother, and his five-year-old sister behind.

When I first met Rizaldi he described himself as being from an “unpretentious background.” Before the tsunami, his father sold produce at the traditional market, his mother tended house, and his brother was studying at a technical high school to become a motorbike mechanic. They lived a simple life, but Rizaldi had great respect for his parents, especially his mother, who taught him extra lessons after school and checked his homework every night.

At the time of the tsunami, Rizaldi had already distinguished himself in Emperom’s middle school and been offered a scholarship to a prestigious private high school in Banda Aceh, the capital city, 15 km. away. However, he had declined the award because his family couldn’t afford the daily bus fare. Still, his parents had decided to enroll him in an academic high school, rather than a technical school like his brother, ambitious that he could win a university scholarship and provide for their old age.

Even as a thirteen-year-old boy, Rizaldi was unsatisfied with anything but perfect marks in school. He understood that it was his responsibility to improve his parents’ lives.

At 7:15 a.m., Rizaldi asked permission from his mother to read the Koran at the balai ngaji. (A balai ngaji is a small informal mosque built in villages without a large enough population to fund a full-sized house of worship.) She wrapped a lunch of rice and salted fish in banana leaves for him. He kissed her hand and scampered outside leaving her, his brother, and his five-year-old sister behind.

~

When the first earthquake struck the loudspeakers bolted into the corners of the balai ngaji fell, shattering on the tiles, and stacks of Korans avalanched off bookshelves, spilling onto Rizaldi. The floor shook so violently that he and the rest of the worshipers were forced to lie down to stop from sliding around. As the wooden building shuddered and groaned, they prayed aloud, their words overlapping to form a single greater appeal.

After the tremor finally subsided, the worshipers stumbled outside to discover palm trees uprooted, the town’s brick houses collapsed or precariously askew, herds of disoriented goats and cows stampeding in circles, and the streets filling with villagers bemoaning the devastation.

Less than two minutes after the first upheaval ended, the second began. As the earth rattled, someone started to sing the azan, the Islamic call to prayer.

Unlike the mutter of Latin mass or the atonal chant of Buddhist monks, the azan is operatic and impressionistic, existing somewhere between prayer and keening song. Though the azan always employs the same words, each muezzin sings them differently, elongating favorite vowels, pitching different words to various keys, enlivening the familiar prayer like jazz musicians tweaking standards. Lā ilāha illallāh—a river of assonance and consonance too beautiful not to sing—ends the azan. Its meaning: there is no god, but God.

Rizaldi concentrated on the azan. The more he focused on the prayer and on Allah, the weaker the quake seemed. Soon the earth stilled. But the azan continued echoing over the wreckage. The villagers instinctively obeyed the call, picking their way toward the balai, which stood tall amid the destruction. Rizaldi saw his family staggering towards him. His brother limped, clutching his bloody shin, and his mother carried his little sister, who was weeping on her shoulder.

The third earthquake was the strongest, hurling everyone to the ground. Babies howled, children screamed, and the grownups started praying again as the world trembled. The azan wailed on mournfully. But mixed in with the azan was a new low rumble, like the earth was growling, “or the sound of an airplane engine.” The roar intensified until they could feel it in their bones. Then they saw the tsunami.

The wave reared higher than the palm trees and was so thick with mud and silt it was nearly black. Fragments of everything it had already consumed—houses, trees, cars, humans—swirled in it. “When I saw the water, I thought I must run. But not even a motorcycle could escape it.” The crowd tried to flee. In the stampede, Rizaldi fought to stay close to his family. His brother disappeared in the mob. He lurched after his mother and sister into a garden of banana trees. His mother and sister were holding hands; their knuckles were white. He wanted to link his fingers with theirs, but then he felt the cold wind pushed ahead of the water tickle the back of his neck.

“When the wave hit me—I fell unconscious. I woke up at the surface. I thought, I must save myself. Then I thought: Where are my mother and sister? The water was so high my feet could not reach the ground. I grabbed onto a floating board. I cannot swim so I was very afraid of losing the board. I believe an angel saved me.”

Rizaldi floated above the ruins of his town, scrutinizing the debris—uprooted trees, a dead cow, the wavy aluminum roofing of a house. The water was so thick with churned mud that he could not see his own chest. Flecks of mica and other minerals hung in the silt, winking in the sunlight. He probed with his toe but could not feel anything. His mother and sister had been right beside him. His mother had been holding his sister’s hand. For all that he could tell he was the only survivor in a drowned world. He did not see many corpses immediately. Bodies usually do not surface until several days after drowning, if at all, when the bacteria consuming the innards have released enough oxygen to bloat the flesh.

Little by little, over the course of an hour, the water receded. Rizaldi was surprised to dangle off his board and be able to toe the muddy ground. When the water sloshed around his waist he let go. Further out the ocean was calm, unimaginably flat and innocent, with only the faintest wind-swell. Wisps of cirrus cloud—favorites of Indonesian fishermen because they promise long spells of good weather—dabbed the sky.

Exhausted, Rizaldi sat on the trunk of a collapsed mango tree. For an hour he watched the black water flow back towards the ocean. When it was gone he stared at the mud. Everything was covered in sludge, inches thick. He didn’t see anyone else. “I was thinking, but not thinking, at that time.”

Around ten o’clock he noticed movement. He didn’t recognize the survivors gathering at the top of a nearby hill. It was almost difficult to tell they were human they were so crusted with muck. Only when he approached did he identify his neighbors. “Have you seen my mother or my sister?” he kept asking. Everyone repeated a variation of that question. Many people were mumbling prayers.

The group walked towards the main road. The landscape had been scalped featureless by the wave, neither trees nor houses had endured, but as they stumbled inland they came across buildings which had remained standing. The edge of Emperom farthest from the ocean had been flooded, but not leveled, by the tsunami. It was there, in the shade of a corner store where Rizaldi had often bought penny candy that he found his brother. Both were too shocked to do anything besides nod in acknowledgement and begin walking side by side.

The exodus continued, swelling as more survivors joined. The tsunami had covered the road in debris—wooden beams, piles of shattered brick, overturned cars and motorbikes—so progress was slow. “While we were walking, I came across many corpses: some men, although women, the elderly, and the very young outnumbered them.” Often Rizaldi recognized their faces: they were the people he had grown up his entire life with.

One of the most unforgettable things about photographs of the tsunami’s aftermath is the positions of the corpses: tangled in the branches of a tree, their limbs dangling, or wedged under an overturned car in a slot too thin for a man to crawl into even if he wanted to. Neither the strong, nor the swift, nor the wise had escaped: only the lucky.

After the tremor finally subsided, the worshipers stumbled outside to discover palm trees uprooted, the town’s brick houses collapsed or precariously askew, herds of disoriented goats and cows stampeding in circles, and the streets filling with villagers bemoaning the devastation.

Less than two minutes after the first upheaval ended, the second began. As the earth rattled, someone started to sing the azan, the Islamic call to prayer.

Unlike the mutter of Latin mass or the atonal chant of Buddhist monks, the azan is operatic and impressionistic, existing somewhere between prayer and keening song. Though the azan always employs the same words, each muezzin sings them differently, elongating favorite vowels, pitching different words to various keys, enlivening the familiar prayer like jazz musicians tweaking standards. Lā ilāha illallāh—a river of assonance and consonance too beautiful not to sing—ends the azan. Its meaning: there is no god, but God.

Rizaldi concentrated on the azan. The more he focused on the prayer and on Allah, the weaker the quake seemed. Soon the earth stilled. But the azan continued echoing over the wreckage. The villagers instinctively obeyed the call, picking their way toward the balai, which stood tall amid the destruction. Rizaldi saw his family staggering towards him. His brother limped, clutching his bloody shin, and his mother carried his little sister, who was weeping on her shoulder.

The third earthquake was the strongest, hurling everyone to the ground. Babies howled, children screamed, and the grownups started praying again as the world trembled. The azan wailed on mournfully. But mixed in with the azan was a new low rumble, like the earth was growling, “or the sound of an airplane engine.” The roar intensified until they could feel it in their bones. Then they saw the tsunami.

The wave reared higher than the palm trees and was so thick with mud and silt it was nearly black. Fragments of everything it had already consumed—houses, trees, cars, humans—swirled in it. “When I saw the water, I thought I must run. But not even a motorcycle could escape it.” The crowd tried to flee. In the stampede, Rizaldi fought to stay close to his family. His brother disappeared in the mob. He lurched after his mother and sister into a garden of banana trees. His mother and sister were holding hands; their knuckles were white. He wanted to link his fingers with theirs, but then he felt the cold wind pushed ahead of the water tickle the back of his neck.

“When the wave hit me—I fell unconscious. I woke up at the surface. I thought, I must save myself. Then I thought: Where are my mother and sister? The water was so high my feet could not reach the ground. I grabbed onto a floating board. I cannot swim so I was very afraid of losing the board. I believe an angel saved me.”

Rizaldi floated above the ruins of his town, scrutinizing the debris—uprooted trees, a dead cow, the wavy aluminum roofing of a house. The water was so thick with churned mud that he could not see his own chest. Flecks of mica and other minerals hung in the silt, winking in the sunlight. He probed with his toe but could not feel anything. His mother and sister had been right beside him. His mother had been holding his sister’s hand. For all that he could tell he was the only survivor in a drowned world. He did not see many corpses immediately. Bodies usually do not surface until several days after drowning, if at all, when the bacteria consuming the innards have released enough oxygen to bloat the flesh.

Little by little, over the course of an hour, the water receded. Rizaldi was surprised to dangle off his board and be able to toe the muddy ground. When the water sloshed around his waist he let go. Further out the ocean was calm, unimaginably flat and innocent, with only the faintest wind-swell. Wisps of cirrus cloud—favorites of Indonesian fishermen because they promise long spells of good weather—dabbed the sky.

Exhausted, Rizaldi sat on the trunk of a collapsed mango tree. For an hour he watched the black water flow back towards the ocean. When it was gone he stared at the mud. Everything was covered in sludge, inches thick. He didn’t see anyone else. “I was thinking, but not thinking, at that time.”

Around ten o’clock he noticed movement. He didn’t recognize the survivors gathering at the top of a nearby hill. It was almost difficult to tell they were human they were so crusted with muck. Only when he approached did he identify his neighbors. “Have you seen my mother or my sister?” he kept asking. Everyone repeated a variation of that question. Many people were mumbling prayers.

The group walked towards the main road. The landscape had been scalped featureless by the wave, neither trees nor houses had endured, but as they stumbled inland they came across buildings which had remained standing. The edge of Emperom farthest from the ocean had been flooded, but not leveled, by the tsunami. It was there, in the shade of a corner store where Rizaldi had often bought penny candy that he found his brother. Both were too shocked to do anything besides nod in acknowledgement and begin walking side by side.

The exodus continued, swelling as more survivors joined. The tsunami had covered the road in debris—wooden beams, piles of shattered brick, overturned cars and motorbikes—so progress was slow. “While we were walking, I came across many corpses: some men, although women, the elderly, and the very young outnumbered them.” Often Rizaldi recognized their faces: they were the people he had grown up his entire life with.

One of the most unforgettable things about photographs of the tsunami’s aftermath is the positions of the corpses: tangled in the branches of a tree, their limbs dangling, or wedged under an overturned car in a slot too thin for a man to crawl into even if he wanted to. Neither the strong, nor the swift, nor the wise had escaped: only the lucky.

~

Filling the headers of the diary’s pages were illustrations and prayers. One drawing titled “The Citizens Walking on the Main Road” showed two groups of figures approaching each other, everyone throwing up their arms—it was hard to tell if they were excited at the encounter or exclaiming over the corpses on the roadside. The prayers decorating the headers of the next two pages displayed Latinate Indonesian above twirls of Arabic: “We must happily give thanks to God!” and “Warnings from God on earth are better than warnings from God at the final judgment.”

~

The brothers followed the crowd to Ajun Mosque, which had been converted into an improvised disaster relief center, in the neighboring town of West Lamteumen. They asked if anyone had seen their mother or younger sister. No one had.

On the steps of the mosque they sat and watched the wounded being carried in, some on tarps and bamboo stretchers, others hobbling with an arm over another person’s shoulder. People were checking the faces of the corpses laid in neat rows across the courtyard; every few minutes someone would scream with grief. “We’ve got to leave,” Rizaldi’s brother said.

The brothers began to walk south on the main road toward their grandmother’s house in East Lamteumen Village, reasoning that it was too far from shore to have been struck by the tsunami. “We felt exhausted, thirsty, shocked, and sad—all of these mixed into one emotion.” People crowded the street, fleeing inland or searching for family.

As the brothers picked their way through jagged broken boards, fallen lamp posts, and a herd of drowned cows, they learned that the tsunami had also inundated East Lamteumen. They stopped and squatted in the shade of an overturned car.

“Where should we go?” they asked each other, but quickly fell silent. There was nowhere left. For all they knew, they were the last members of their family alive.

Already, dogs were sniffing the dead bodies in the streets, chickens pecking at the inert flesh. For months afterwards, many inhabitants of Banda Aceh refused to eat chicken.

Then the brothers heard their names being called. Later, listing the moments during the aftermath of the tsunami for which he was thankful, Rizaldi rated his uncle’s miraculous appearance as high as the board he clung to while the wave swirled below him. He had hardly believed anyone in his family was still alive, let alone that they could rescue him.

The uncle took his nephews under his arms and steered them south towards his village, Ateuk. Just before Ateuk they crossed a line: the farthest extent the tsunami had reached, marked by a layer of mud and debris. Within an inch, the grass went from silted, rumpled, to green and healthy. Ateuk had escaped the tsunami.

On the steps of the mosque they sat and watched the wounded being carried in, some on tarps and bamboo stretchers, others hobbling with an arm over another person’s shoulder. People were checking the faces of the corpses laid in neat rows across the courtyard; every few minutes someone would scream with grief. “We’ve got to leave,” Rizaldi’s brother said.

The brothers began to walk south on the main road toward their grandmother’s house in East Lamteumen Village, reasoning that it was too far from shore to have been struck by the tsunami. “We felt exhausted, thirsty, shocked, and sad—all of these mixed into one emotion.” People crowded the street, fleeing inland or searching for family.

As the brothers picked their way through jagged broken boards, fallen lamp posts, and a herd of drowned cows, they learned that the tsunami had also inundated East Lamteumen. They stopped and squatted in the shade of an overturned car.

“Where should we go?” they asked each other, but quickly fell silent. There was nowhere left. For all they knew, they were the last members of their family alive.

Already, dogs were sniffing the dead bodies in the streets, chickens pecking at the inert flesh. For months afterwards, many inhabitants of Banda Aceh refused to eat chicken.

Then the brothers heard their names being called. Later, listing the moments during the aftermath of the tsunami for which he was thankful, Rizaldi rated his uncle’s miraculous appearance as high as the board he clung to while the wave swirled below him. He had hardly believed anyone in his family was still alive, let alone that they could rescue him.

The uncle took his nephews under his arms and steered them south towards his village, Ateuk. Just before Ateuk they crossed a line: the farthest extent the tsunami had reached, marked by a layer of mud and debris. Within an inch, the grass went from silted, rumpled, to green and healthy. Ateuk had escaped the tsunami.

~

By 11 a.m. the brothers had arrived at their uncle’s home. Rizaldi’s aunt and cousins buried him in a hug. He clung to his aunt even when she tried to gently disengage. He glanced over her shoulder, hoping to see his father, his mother, or his little sister. But no one else ran towards him from the house.

Rizaldi began to shake so hard that his family thought he was beginning to have a seizure, which he had suffered from occasionally in the past, and grabbed hold of his limbs. He remembered the leaves of the banana trees waving in the wind pushed before the tsunami, his mother’s and sister’s heads swiveling to look at the water. The impact of the wave had felt like being run over by a bulldozer. Could his fragile mother, his five-year-old sister have survived that?

As Rizaldi came to, he realized that if his aunt and cousins were alive, if he was alive, his parents and sister might have survived too. They could be picking through the ruins of Emperom right now, looking for him. They might be lying wounded under the rubble, calling for help.

He wanted to start searching immediately, but his aunt and uncle sat him down and brought him food and water. He gulped down three glasses of water and a plate of rice. Then his aunt and uncle asked to hear what had happened to him.

“After telling our stories to my uncle and his family, I felt more natural. Until that time we had only been answered with sadness and horror. But there was my family! They ordered us to bathe with clean water, because our clothes, even our faces, were filthy with mud from the tsunami, and my body was still red, sore, and swollen from being hit by the tsunami.”

Naked, free of the ruined clothes, the mud washed away, Rizaldi still felt soiled.

Rizaldi began to shake so hard that his family thought he was beginning to have a seizure, which he had suffered from occasionally in the past, and grabbed hold of his limbs. He remembered the leaves of the banana trees waving in the wind pushed before the tsunami, his mother’s and sister’s heads swiveling to look at the water. The impact of the wave had felt like being run over by a bulldozer. Could his fragile mother, his five-year-old sister have survived that?

As Rizaldi came to, he realized that if his aunt and cousins were alive, if he was alive, his parents and sister might have survived too. They could be picking through the ruins of Emperom right now, looking for him. They might be lying wounded under the rubble, calling for help.

He wanted to start searching immediately, but his aunt and uncle sat him down and brought him food and water. He gulped down three glasses of water and a plate of rice. Then his aunt and uncle asked to hear what had happened to him.

“After telling our stories to my uncle and his family, I felt more natural. Until that time we had only been answered with sadness and horror. But there was my family! They ordered us to bathe with clean water, because our clothes, even our faces, were filthy with mud from the tsunami, and my body was still red, sore, and swollen from being hit by the tsunami.”

Naked, free of the ruined clothes, the mud washed away, Rizaldi still felt soiled.

~

Rizaldi’s uncle, cousins, and older brother returned to Emperom to search for his missing parents. Rizaldi had intended to join, but he had been paralyzed by an agonizing migraine. So he and his aunt were alone when the aftershocks struck. He grabbed a box of instant noodles for provisions and rushed outside with his aunt into the packed streets. A yell echoed over the crowd: “The water’s rising!”

“Excuse me,” he said, as someone shoved him.

Then everyone was screaming, throwing elbows, clawing at each other, desperate in their struggle to reach the road leading away from the sea. In the crush Rizaldi slipped. Shoes pounded him. His aunt’s hand appeared and dragged him upright. They fled with the crowd. Soon, they were out of breath and lagging far behind everyone else, but no tsunami appeared.

Rizaldi and his aunt followed the crowd to the next village, Lambaro, before they had to sit from exhaustion. There was no food and water; “Above all, the rays of the sun stabbed us.” A rumor circulated through the refugees that someone had yelled the warning as a joke; “Surely that person was very cruel to say such a thing.”

“Excuse me,” he said, as someone shoved him.

Then everyone was screaming, throwing elbows, clawing at each other, desperate in their struggle to reach the road leading away from the sea. In the crush Rizaldi slipped. Shoes pounded him. His aunt’s hand appeared and dragged him upright. They fled with the crowd. Soon, they were out of breath and lagging far behind everyone else, but no tsunami appeared.

Rizaldi and his aunt followed the crowd to the next village, Lambaro, before they had to sit from exhaustion. There was no food and water; “Above all, the rays of the sun stabbed us.” A rumor circulated through the refugees that someone had yelled the warning as a joke; “Surely that person was very cruel to say such a thing.”

~

All the corpses were being brought to Lambaro. The emergency authorities, afraid of contagion, were paying 100,000 rp., about $10 USA, a princely sum, for each body brought to Lambaro’s mass grave. “There were thousands of corpses all swelling and puffing up.” The deceased were laid out in neat rows. There had been body bags for the first few hundred corpses but the bags had run out so workers had shrouded the dead with blankets, then shirts, then ripped-down advertising banners, before they had given up and left their naked faces staring at the sky. The uncovered corpses looked especially terrible because mud and silt had colored their skin an ashen gray. Rizaldi and his aunt sat beneath a tree, watching people arrive with stacks of bodies in pickup trucks or slung over the backs of water buffalos or horses.

Eventually, their cousin Imam found them and brought them to his house. When Rizaldi walked through the door he almost collapsed: his father, his brother, six cousins, his uncle, and more relatives were gathered there. In the lineup of ecstatic faces he immediately noticed two gaping absences.

Eventually, their cousin Imam found them and brought them to his house. When Rizaldi walked through the door he almost collapsed: his father, his brother, six cousins, his uncle, and more relatives were gathered there. In the lineup of ecstatic faces he immediately noticed two gaping absences.

~

My first impression of Rizaldi was that he had been shaken very badly right before meeting me—maybe narrowly avoiding an accident on his motorbike—and was just recovering his composure. When he introduced himself his movements were jerky, his handshake limp. He rushed through his sentences, his words almost rear-ending each other. There was a strange intensity to his speech, as if he was imparting a secret, yet his tone was without affect, neither rising nor falling. He had heard I was a writer interested in the tsunami and invited himself to lunch.

When I took Rizaldi out for a meal about a week later, he ordered an extra-large portion of fried rice then ate almost nothing. He was skeletally skinny, with a poof of fluffy dry hair, and a smile that showed off crooked incisors. He ended most sentences with a shrill laugh or an exclamation like, “Oh, I shouldn’t have said that,” or, “I know I should do better.” Out of the blue he declared, “I’m such a bad person, such a terrible person.” He fidgeted constantly, his fingers drumming the tabletop, his foot tapping the table’s legs. He admitted that he didn’t like the other students at his university: he thought they sneered at him behind his back for being poor and awkward. He avoided my gaze, but during our conversation watched what seemed to be an invisible fly circling over my shoulders. “My problem,” he told me, “is that I can’t control my emotions.”

When I took Rizaldi out for a meal about a week later, he ordered an extra-large portion of fried rice then ate almost nothing. He was skeletally skinny, with a poof of fluffy dry hair, and a smile that showed off crooked incisors. He ended most sentences with a shrill laugh or an exclamation like, “Oh, I shouldn’t have said that,” or, “I know I should do better.” Out of the blue he declared, “I’m such a bad person, such a terrible person.” He fidgeted constantly, his fingers drumming the tabletop, his foot tapping the table’s legs. He admitted that he didn’t like the other students at his university: he thought they sneered at him behind his back for being poor and awkward. He avoided my gaze, but during our conversation watched what seemed to be an invisible fly circling over my shoulders. “My problem,” he told me, “is that I can’t control my emotions.”

~

When an organization like the Red Cross, OxFam, or Save the Children responds to a catastrophe time is pressing and information scarce. Thus, NGOs employ checklists to organize their response and make sure the essential needs of survivors are met. These lists usually start with basics like food and water, and continue to things like emergency shelters and prophylactics, such as portable “honey bucket” toilets and bottles of hand sanitizer, to prevent outbreaks of disease in refugee camps. If mental health is even on the list, it is very near the bottom.

In many ways, this prioritizing makes sense. Food, water, and shelter are immediate needs. For donors and NGO workers those items are tangible, quantifiable help that can be listed on fundraising letters.

After the tsunami, the international community reacted to Aceh’s disaster with unprecedented generosity. Help came not just in immediate emergency relief—food, medicine, and the construction of refugee camps—but extended over a six-year program orchestrated by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Over 14 billion USA dollars were donated; the UK public alone gave over $600,000,000, or around $10 for every citizen. Whole villages were rebuilt by donor countries; Banda Aceh’s “Turk Town” and “China Town” are named after the countries who built them, not their inhabitants. In total, more than 1,000 miles of road and 100,000 houses were constructed.

But little attention was paid to mental healthcare.

The tsunami killed over 60,000 individuals in Banda Aceh—or about a fourth of the population. Many towns along Aceh province’s west coast were struck even harder—up to 95% of the residents of some villages died. Everyone lost someone important to them. Most people witnessed friends or family swept away by the tsunami and heard their screams. Nearly everyone saw some of the 120,000 corpses while they lay in the streets or as they were collected, sometimes with bare hands, sometimes by pushing them into piles with bulldozers.

Four of the primary triggers of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are: 1) being involved in a catastrophic event, 2) watching family or friends be seriously hurt or perish, 3) abruptly losing loved ones (especially many at once), and 4) prolonged exposure to the corpses of people an individual cared about. Almost everyone in Banda Aceh experienced these triggers. Further exacerbating the risk for mental illness were the impoverished, uncertain, and dislocated lives tsunami victims led afterwards in refugee camps.

PTSD is a serious psychological disorder that can last for decades or even a lifetime. It affects an individual’s ability to control his or her feelings, sometimes leading to mood-swings and fits of violence, and often causes emotional numbing, from sobering cases of the blues to suicidal despair.

After the tsunami several NGOs provided short term PTSD counseling. Two, Save the Children and Northwest Medical Teams, offered art therapy for children. Others tried to get children to talk about their experiences using hand puppets. But everyone except the Norwegian Red Cross had gone home within a year.

Kaz de Jong, head of mental health services for Medicins Sans Frontieres (MSF, also known as Doctors Without Borders), acknowledged, "In areas like mental healthcare, which is not a high priority for development agencies, that third stage of somehow passing it along to someone else is seldom really done."

Local facilities were unprepared to handle any trauma lingering in the population. At the time of the tsunami, there was only one mental health facility in all of Aceh province, located in Banda Aceh. It had four fulltime psychiatrists serving the region’s four-million residents. The tsunami flooded the Aceh Psychiatric Hospital and many of its approximately 300 patents vanished in the ensuing chaos. The hospital did not return to full operation until three years later with the help of the Norwegian Red Cross. Though many Indonesian medical workers, including counselors, volunteered in Aceh immediately after the tsunami, most had returned home within a few months.

Today, it’s almost impossible to tell that Banda Aceh was devastated seven years ago. Ironically, the most salient evidence of the tsunami is that the capital looks fresher than most Indonesian cities: (nearly) pothole-less roads, swooping modern bridges, and whole blocks of UN-built houses, each an exact clone of the next, contrast with the drab Soviet-like architecture that survived the wave. In 2010, the UNDP declared, “Aceh has been rebuilt, and in some ways rebuilt better.” Only the observant will notice a Brazilian flag painted on a university lecture hall, or the European Union’s halo of stars emblazoned on a city garbage truck, or a white and blue UN pickup truck honking a herd of cows out of its way. Even fewer will note the mass graveyards and the plaques memorializing the tsunami in every town, now largely overgrown, hidden under sprouting brush.

In many ways, this prioritizing makes sense. Food, water, and shelter are immediate needs. For donors and NGO workers those items are tangible, quantifiable help that can be listed on fundraising letters.

After the tsunami, the international community reacted to Aceh’s disaster with unprecedented generosity. Help came not just in immediate emergency relief—food, medicine, and the construction of refugee camps—but extended over a six-year program orchestrated by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Over 14 billion USA dollars were donated; the UK public alone gave over $600,000,000, or around $10 for every citizen. Whole villages were rebuilt by donor countries; Banda Aceh’s “Turk Town” and “China Town” are named after the countries who built them, not their inhabitants. In total, more than 1,000 miles of road and 100,000 houses were constructed.

But little attention was paid to mental healthcare.

The tsunami killed over 60,000 individuals in Banda Aceh—or about a fourth of the population. Many towns along Aceh province’s west coast were struck even harder—up to 95% of the residents of some villages died. Everyone lost someone important to them. Most people witnessed friends or family swept away by the tsunami and heard their screams. Nearly everyone saw some of the 120,000 corpses while they lay in the streets or as they were collected, sometimes with bare hands, sometimes by pushing them into piles with bulldozers.

Four of the primary triggers of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are: 1) being involved in a catastrophic event, 2) watching family or friends be seriously hurt or perish, 3) abruptly losing loved ones (especially many at once), and 4) prolonged exposure to the corpses of people an individual cared about. Almost everyone in Banda Aceh experienced these triggers. Further exacerbating the risk for mental illness were the impoverished, uncertain, and dislocated lives tsunami victims led afterwards in refugee camps.

PTSD is a serious psychological disorder that can last for decades or even a lifetime. It affects an individual’s ability to control his or her feelings, sometimes leading to mood-swings and fits of violence, and often causes emotional numbing, from sobering cases of the blues to suicidal despair.

After the tsunami several NGOs provided short term PTSD counseling. Two, Save the Children and Northwest Medical Teams, offered art therapy for children. Others tried to get children to talk about their experiences using hand puppets. But everyone except the Norwegian Red Cross had gone home within a year.

Kaz de Jong, head of mental health services for Medicins Sans Frontieres (MSF, also known as Doctors Without Borders), acknowledged, "In areas like mental healthcare, which is not a high priority for development agencies, that third stage of somehow passing it along to someone else is seldom really done."

Local facilities were unprepared to handle any trauma lingering in the population. At the time of the tsunami, there was only one mental health facility in all of Aceh province, located in Banda Aceh. It had four fulltime psychiatrists serving the region’s four-million residents. The tsunami flooded the Aceh Psychiatric Hospital and many of its approximately 300 patents vanished in the ensuing chaos. The hospital did not return to full operation until three years later with the help of the Norwegian Red Cross. Though many Indonesian medical workers, including counselors, volunteered in Aceh immediately after the tsunami, most had returned home within a few months.

Today, it’s almost impossible to tell that Banda Aceh was devastated seven years ago. Ironically, the most salient evidence of the tsunami is that the capital looks fresher than most Indonesian cities: (nearly) pothole-less roads, swooping modern bridges, and whole blocks of UN-built houses, each an exact clone of the next, contrast with the drab Soviet-like architecture that survived the wave. In 2010, the UNDP declared, “Aceh has been rebuilt, and in some ways rebuilt better.” Only the observant will notice a Brazilian flag painted on a university lecture hall, or the European Union’s halo of stars emblazoned on a city garbage truck, or a white and blue UN pickup truck honking a herd of cows out of its way. Even fewer will note the mass graveyards and the plaques memorializing the tsunami in every town, now largely overgrown, hidden under sprouting brush.

~

For three days after the tsunami, Rizaldi woke before dawn and spent the day searching for his mother and sister. But he did not even meet anyone who claimed to have seen them alive.

On the fourth day Rizaldi refused to leave his uncle’s house. He remained sitting on the floor with his back against the wall. When family members tried to speak to him, he stared blankly into space.

At 3 p.m. his uncle ran in, exclaiming that Rizaldi’s mother had been found—she was in Rizaldi grandmother’s room in Ketapang.

“My father and I went immediately to Ketapang. The instant we were there, I sprinted inside and I saw my mother, lying on a cot, sick. The three of us [Rizaldi, his father, and mother], were very joyful.” Rizaldi only released his mother from his hug to look for his sister, excited to hoist her into the air and twirl her around. My sister must be in the bathroom, he thought, because my mother was holding her hand when the tsunami hit them and my mother would never have let go. Then he saw his mother weeping in his father’s arms and knew he could never mention his sister in his mother’s presence again.

Rizaldi barely left his mother’s side for the rest of the day. She seemed so fragile. He wanted to care for her. He slept that night on the floor beside her bed.

The next day, the family brought Rizaldi’s mother to the hospital. Because all the beds were filled, nurses provided them with a lounger. The doctors examined her, but could not discover the cause of the pain in her head and spine or the source of her exhaustion. They were worried enough to ask that she sleep at the hospital for monitoring.

Despite Rizaldi’s protests, he wasn’t given permission to stay with her because his father was afraid he would catch a sickness from the other patients.

On the fourth day Rizaldi refused to leave his uncle’s house. He remained sitting on the floor with his back against the wall. When family members tried to speak to him, he stared blankly into space.

At 3 p.m. his uncle ran in, exclaiming that Rizaldi’s mother had been found—she was in Rizaldi grandmother’s room in Ketapang.

“My father and I went immediately to Ketapang. The instant we were there, I sprinted inside and I saw my mother, lying on a cot, sick. The three of us [Rizaldi, his father, and mother], were very joyful.” Rizaldi only released his mother from his hug to look for his sister, excited to hoist her into the air and twirl her around. My sister must be in the bathroom, he thought, because my mother was holding her hand when the tsunami hit them and my mother would never have let go. Then he saw his mother weeping in his father’s arms and knew he could never mention his sister in his mother’s presence again.

Rizaldi barely left his mother’s side for the rest of the day. She seemed so fragile. He wanted to care for her. He slept that night on the floor beside her bed.

The next day, the family brought Rizaldi’s mother to the hospital. Because all the beds were filled, nurses provided them with a lounger. The doctors examined her, but could not discover the cause of the pain in her head and spine or the source of her exhaustion. They were worried enough to ask that she sleep at the hospital for monitoring.

Despite Rizaldi’s protests, he wasn’t given permission to stay with her because his father was afraid he would catch a sickness from the other patients.

~

Rizaldi’s mother did not improve. The mysterious pain thundered in her head and spread to her chest. The nurses moved her to a bed where she barely sat up, even to eat. Mostly she cried.

Paralyzing guilt is often a symptom of PTSD as victims wonder if they somehow deserved the catastrophe. Kaz de Jong, MSF’s director of mental health services, described the situation shortly after the tsunami as follows:

“Everybody is reacting differently. Some people are doing pretty well, for others it will take longer… Some people say they do not want to live anymore and they panic that it [the tsunami] is coming back and then when they wake up they get flashbacks… Some people can’t sleep, or can’t stop crying and there are people with problems of guilt. They say: ‘I could keep hold of two of my children, but I had to let the other one go, why did I choose the one I did?’

After the tsunami, the idea that natural disaster was punishment for Aceh’s misdeeds took hold of the whole province. Many Acehnese religious leaders preached the idea from the pulpit. Even today, if you ask people about the tsunami they will often begin by saying, “It was sent as retribution for our sins…”

Paralyzing guilt is often a symptom of PTSD as victims wonder if they somehow deserved the catastrophe. Kaz de Jong, MSF’s director of mental health services, described the situation shortly after the tsunami as follows:

“Everybody is reacting differently. Some people are doing pretty well, for others it will take longer… Some people say they do not want to live anymore and they panic that it [the tsunami] is coming back and then when they wake up they get flashbacks… Some people can’t sleep, or can’t stop crying and there are people with problems of guilt. They say: ‘I could keep hold of two of my children, but I had to let the other one go, why did I choose the one I did?’

After the tsunami, the idea that natural disaster was punishment for Aceh’s misdeeds took hold of the whole province. Many Acehnese religious leaders preached the idea from the pulpit. Even today, if you ask people about the tsunami they will often begin by saying, “It was sent as retribution for our sins…”

~

One risk factor for adolescents with PTSD is having parents who suffer from the same illness. Some studies show that recovery rates for adolescents suffering from PTSD are halved if their caretakers are afflicted as well.

Rizaldi’s mother eventually left the hospital. The pain in her spine and chest never completely faded, though doctors were unable to explain its source. Through the following years she was intermittently leveled by bouts of exhaustion. She never talked about her lost daughter again.

After the tsunami, Rizaldi’s father was too “traumatized to continue selling vegetables in [the traditional market] Pasar Seutui, because when the tsunami happened, he was there.” Even when he could not find another job for two years, he still refused to sell produce again. The family could not afford their own house after the refugee camps closed, so they had to move in with cousins. Eventually, Rizaldi’s father found work as a janitor at Banda Aceh’s hospital, but he detested it, often spending the evenings complaining about the trash he had to pick up and the disrespectfulness of the patients and their families. Before the tsunami he had been a plump man who laughed often, but afterwards he smoked three packs of Indonesian clove cigarettes a day and dwindled to a skeleton, so thin Rizaldi could count the knobs of his spine in the back of his neck.

Rizaldi’s mother eventually left the hospital. The pain in her spine and chest never completely faded, though doctors were unable to explain its source. Through the following years she was intermittently leveled by bouts of exhaustion. She never talked about her lost daughter again.

After the tsunami, Rizaldi’s father was too “traumatized to continue selling vegetables in [the traditional market] Pasar Seutui, because when the tsunami happened, he was there.” Even when he could not find another job for two years, he still refused to sell produce again. The family could not afford their own house after the refugee camps closed, so they had to move in with cousins. Eventually, Rizaldi’s father found work as a janitor at Banda Aceh’s hospital, but he detested it, often spending the evenings complaining about the trash he had to pick up and the disrespectfulness of the patients and their families. Before the tsunami he had been a plump man who laughed often, but afterwards he smoked three packs of Indonesian clove cigarettes a day and dwindled to a skeleton, so thin Rizaldi could count the knobs of his spine in the back of his neck.

~

While Rizaldi was attending his mother at the hospital, he met many foreign volunteers, including his mother’s doctors.

“The people who investigated my mother were Australian and New Zealanders. Although I couldn’t speak much English, I tried to practice speaking with them.” The names of the foreigners were listed in the diary, in all capital letters, “WADE, JAMES, DOOLAN, MCDONALD, MURRAY, MICHAEL, CAMPNY, ROBERTSON, BROWN. I studied a lot of English with them and I taught them Acehnese and Indonesian. Really, it’s an experience I can never forget.” The last sentence was heavily underlined. He even recalled the day the volunteers left, the 13th of January, 2005.

“The people who investigated my mother were Australian and New Zealanders. Although I couldn’t speak much English, I tried to practice speaking with them.” The names of the foreigners were listed in the diary, in all capital letters, “WADE, JAMES, DOOLAN, MCDONALD, MURRAY, MICHAEL, CAMPNY, ROBERTSON, BROWN. I studied a lot of English with them and I taught them Acehnese and Indonesian. Really, it’s an experience I can never forget.” The last sentence was heavily underlined. He even recalled the day the volunteers left, the 13th of January, 2005.

~

One of Rizaldi’s last comments in the diary was a discussion of the eight things he was thankful for during the time of the tsunami. It started with, “Allah’s mercy given to us when facing the disaster of the earthquake and tsunami…,” continued to items like the wooden board that prevented him from drowning and the free medical treatment his mother received “because otherwise the expenses would have been out of reach.” It ended: “I was able to speak directly with foreigners and learn about their cultures and their languages.”

~

Almost seven years later, when I met Rizaldi, he was an English student at the University Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh. Only in his second year, he was already a standout, known for obsessively diligent study habits and ruthlessly proctoring other students’ tests at the university language center.

The last thirty pages of the diary, after the narrative ended, were covered with columns of English, Arabic, and Korean vocabulary words all translated into Bahasa Indonesia. One page displayed a family tree, the captions written in English, the fluid curves of Arabic, and the glyphic boxes of Korean. A few teenager-appropriate doodles were interspersed with the grammatical declensions—Dragon Ball Z characters and sketches of popular soccer players, a page full of attempts to refine his signature—but they were few compared to his study notes. Already his desire to learn the words to tell his story was evident.

The last thirty pages of the diary, after the narrative ended, were covered with columns of English, Arabic, and Korean vocabulary words all translated into Bahasa Indonesia. One page displayed a family tree, the captions written in English, the fluid curves of Arabic, and the glyphic boxes of Korean. A few teenager-appropriate doodles were interspersed with the grammatical declensions—Dragon Ball Z characters and sketches of popular soccer players, a page full of attempts to refine his signature—but they were few compared to his study notes. Already his desire to learn the words to tell his story was evident.

~

About a month after our first conversation, Rizaldi stopped returning my calls or answering my emails and text messages. I was nervous I’d offended him. But one day when I told a mutual friend of my fear, her mouth stretched into an “O” of shock: “You didn’t hear what happened to him?”

Over the course of the last year, she explained, Rizaldi had been acting increasingly erratic. His once sterling grades had degraded, despite what she described as “obsessive” study habits. He’d feuded with co-workers at the university English Language Center, alienating the few friends he’d had. Recently, he’d flunked a pre-examination for a prestigious scholarship to America and had a fit in the testing room, wailing that he was failing his parents. “The last people who saw him were a few of the guys from the office. They said he was so far gone, he didn’t know who they were.”

A week or so before, Rizaldi’s parents had called the English Language Center wondering which friend’s house he’d been sleeping at. Why, they had asked, hadn’t he been considerate enough to call his mother if he was going to stay away so long?

Over the course of the last year, she explained, Rizaldi had been acting increasingly erratic. His once sterling grades had degraded, despite what she described as “obsessive” study habits. He’d feuded with co-workers at the university English Language Center, alienating the few friends he’d had. Recently, he’d flunked a pre-examination for a prestigious scholarship to America and had a fit in the testing room, wailing that he was failing his parents. “The last people who saw him were a few of the guys from the office. They said he was so far gone, he didn’t know who they were.”

A week or so before, Rizaldi’s parents had called the English Language Center wondering which friend’s house he’d been sleeping at. Why, they had asked, hadn’t he been considerate enough to call his mother if he was going to stay away so long?

~

Acehnese culture expects individuals to process grief internally, silently. To share trauma is to appear weak, to lose face, especially if you are a man. Talking about mental illness is especially taboo. Acehnese society views psychiatric problems as Allah’s judgment on an individual and that person’s family. Unwed relations can have difficulty finding partners. Customers might avoid the family’s store or produce from their farm. Acehnese folk wisdom declares, “It is only a problem if you make the problem larger than yourself.”

Nowhere is this reticence more evident than in traditional Acehnese solutions for mental illness: herbal remedies, reciting the Koran, and, especially, the pasung. The pasung is a contraption similar to medieval stocks: wooden hand- or foot-cuffs fashioned out of a single hinged board. Normally, family members clamp a pasung around an ill victim’s feet and chain it to a wall in the family home. The device keeps the potentially unstable individual from causing problems in the village. Even more, once the pasung is locked and the door of the house shut, it’s almost as if the illness—and the individual—doesn’t exist anymore.

But attitudes towards mental health in Aceh are changing slowly. Recently, in 2010, pasungs were banned. Health officials began combing the population, unshackling victims and transporting them to the new psychiatric hospital in Banda Aceh. Laws were passed providing free healthcare to impoverished Acehnese. In an effort to make mental healthcare seem more appealing, the government demolished the hospital’s high walls and did not string barbed wire on the new gates.

Nowhere is this reticence more evident than in traditional Acehnese solutions for mental illness: herbal remedies, reciting the Koran, and, especially, the pasung. The pasung is a contraption similar to medieval stocks: wooden hand- or foot-cuffs fashioned out of a single hinged board. Normally, family members clamp a pasung around an ill victim’s feet and chain it to a wall in the family home. The device keeps the potentially unstable individual from causing problems in the village. Even more, once the pasung is locked and the door of the house shut, it’s almost as if the illness—and the individual—doesn’t exist anymore.

But attitudes towards mental health in Aceh are changing slowly. Recently, in 2010, pasungs were banned. Health officials began combing the population, unshackling victims and transporting them to the new psychiatric hospital in Banda Aceh. Laws were passed providing free healthcare to impoverished Acehnese. In an effort to make mental healthcare seem more appealing, the government demolished the hospital’s high walls and did not string barbed wire on the new gates.

~

When I visited the Banda Aceh Psychiatric Hospital, Dr. Sukma, a kindly, stout psychiatrist, wearing a headscarf decorated with sequins, showed me the facilities. The old hospital had been abandoned but never torn down so its ruins still lurked behind the new Dutch-constructed buildings; the waterline of the tsunami was visible as a stain, up to about the height of my neck, on its walls. Nurses in snowy uniforms and headscarves shepherded ragged men with shaved heads between rooms. As we approached the patients’ dormitories I winced at a sewage-like stink.

“I am a little embarrassed,” Dr. Sukma said, “to admit that we are overcrowded. We only have a limited number of beds, but we don’t turn anyone away, so many patients sleep on the floor. We have beds for maybe 250 patients, but over 700 in residence.”

We peered through observation windows, guarded by rusted iron bars, into a long institutional dormitory filled with metal beds naked of sheets or mattresses; nests of clothing lay on the floor between the cots, even under them, marking where most inmates slept. Graffiti had been carved onto the walls by scratching through the yellow paint to the concrete below.

Patients crowded at the far end of the dorm as orderlies slid plates of rice and bananas through a slot in a barred door to them. A man, his lids open so wide his pupils seemed to float in them like out-of-orbit moons, turned and saw us.

“Mental health is a serious problem here,” Dr. Sukma continued, leading me farther down the hall. “Aceh has a much higher incidence of mental health problems—especially PTSD and acute depression—than the rest of Indonesia. Indexes for anxiety and depression here are around 15% vs. 8.8% for the national average. For individuals affected with psychosis, we have almost four times the national average: 2% vs. 0.45%.”

The wally-eyed man let out a hoot and began to shamble through the rows of beds, heading towards us. The other patients took notice and abandoned their lunches to follow him.

“In America, if people have depression, anxiety, or something else, they know to go to the mental hospital, but here people only think of health for physical things. People will usually go to the normal hospital with psychiatric symptoms—they can’t sleep, they’re having headaches. In Aceh, people don’t even consider the idea that they can have mental trauma. Most people don’t even know what that is. They wouldn’t know what a psychologist is supposed to do. And if something is wrong they don’t want to talk about it. They just keep working on the farm until they break or they get better. That’s Acehnese—that’s Indonesian—culture.”

The wally-eyed man reached the window and gripped the bars. “Tell me why, dammit, tell me why,” he said distinctly in Indonesian, his stunned expression never altering despite the rage in his voice, his pupils continuing their drift.

“Just ignore them,” Sukma said. “It’s going to be a huge problem for Aceh in the future. I was doing work at a coastal village that was hit by the tsunami and every boy in that school still had trauma from the event. Can you imagine what it’s going to be like when those boys grow up? Can you imagine what it’s already like in some of the villages where nearly everyone died and the few survivors saw their families swept away?”

As we walked down the hallway outside the dormitory, patients shoved their hands through the bars, clawing the air. “Cigarettes!” some shouted. “Money! A thousand ribu, only a thousand!” “White man!” A chorus somewhere in the back recited every dirty English word they knew, “Fuck! Shit! Whore!”, before settling on “Fuck!” and screaming it on repeat.

“It’s like a ticking bomb that’s going to go off who knows when. It will be like a second tsunami,” Dr. Sukma said.

An enormously obese man shoved himself into a window well and screamed, “I am not crazy! I am not crazy!” He raked his scab-covered face with one hand and counted prayer beads with the other. Rolls of his fat squished out between the bars. As I slowed to a stop, he began screeching an Islamic prayer in Arabic.

“Don’t look at them—don’t look at them in the eye,” Dr. Sukma ordered.

But I couldn’t stop scrutinizing their howling faces for a familiar puff of dry hair and an off-balance smile with crooked incisors.

“I am a little embarrassed,” Dr. Sukma said, “to admit that we are overcrowded. We only have a limited number of beds, but we don’t turn anyone away, so many patients sleep on the floor. We have beds for maybe 250 patients, but over 700 in residence.”

We peered through observation windows, guarded by rusted iron bars, into a long institutional dormitory filled with metal beds naked of sheets or mattresses; nests of clothing lay on the floor between the cots, even under them, marking where most inmates slept. Graffiti had been carved onto the walls by scratching through the yellow paint to the concrete below.

Patients crowded at the far end of the dorm as orderlies slid plates of rice and bananas through a slot in a barred door to them. A man, his lids open so wide his pupils seemed to float in them like out-of-orbit moons, turned and saw us.

“Mental health is a serious problem here,” Dr. Sukma continued, leading me farther down the hall. “Aceh has a much higher incidence of mental health problems—especially PTSD and acute depression—than the rest of Indonesia. Indexes for anxiety and depression here are around 15% vs. 8.8% for the national average. For individuals affected with psychosis, we have almost four times the national average: 2% vs. 0.45%.”

The wally-eyed man let out a hoot and began to shamble through the rows of beds, heading towards us. The other patients took notice and abandoned their lunches to follow him.

“In America, if people have depression, anxiety, or something else, they know to go to the mental hospital, but here people only think of health for physical things. People will usually go to the normal hospital with psychiatric symptoms—they can’t sleep, they’re having headaches. In Aceh, people don’t even consider the idea that they can have mental trauma. Most people don’t even know what that is. They wouldn’t know what a psychologist is supposed to do. And if something is wrong they don’t want to talk about it. They just keep working on the farm until they break or they get better. That’s Acehnese—that’s Indonesian—culture.”

The wally-eyed man reached the window and gripped the bars. “Tell me why, dammit, tell me why,” he said distinctly in Indonesian, his stunned expression never altering despite the rage in his voice, his pupils continuing their drift.

“Just ignore them,” Sukma said. “It’s going to be a huge problem for Aceh in the future. I was doing work at a coastal village that was hit by the tsunami and every boy in that school still had trauma from the event. Can you imagine what it’s going to be like when those boys grow up? Can you imagine what it’s already like in some of the villages where nearly everyone died and the few survivors saw their families swept away?”

As we walked down the hallway outside the dormitory, patients shoved their hands through the bars, clawing the air. “Cigarettes!” some shouted. “Money! A thousand ribu, only a thousand!” “White man!” A chorus somewhere in the back recited every dirty English word they knew, “Fuck! Shit! Whore!”, before settling on “Fuck!” and screaming it on repeat.

“It’s like a ticking bomb that’s going to go off who knows when. It will be like a second tsunami,” Dr. Sukma said.

An enormously obese man shoved himself into a window well and screamed, “I am not crazy! I am not crazy!” He raked his scab-covered face with one hand and counted prayer beads with the other. Rolls of his fat squished out between the bars. As I slowed to a stop, he began screeching an Islamic prayer in Arabic.

“Don’t look at them—don’t look at them in the eye,” Dr. Sukma ordered.

But I couldn’t stop scrutinizing their howling faces for a familiar puff of dry hair and an off-balance smile with crooked incisors.

~

In the diary, below “Tamat” (“the end” in Indonesian), was a carefully alphabetized list of Rizaldi’s family members, stretching eighteen names long and finishing with “Gustina Sari, my younger sister: lost.” Rizaldi was very careful to use “lost” for people whose corpses were never found, as opposed to “deceased” for bodies that had been identified.

~

After Rizaldi disappeared, I visited the tsunami memorial and mass grave in Lohkgna, a town close to his former home in Emperom. Despite accurate directions from a local, I drove past the memorial twice before discovering the gate, smothered in overgrowth. The earth beneath the entrance had heaved up, scattering bricks. Inside, the trail was pinched so thin by immature forest—ferns, grasses, sprouting trees—that I had to turn sideways to squeeze through the brush. Insects raised a cacophony and, above that, clear and sweet, I discerned three different types of bird song. I noticed wild pig tracks at the edge of a muddy puddle.

As I batted aside branches, I wondered whether Rizaldi’s sister rested here. If her body hadn’t been sucked into the ocean by the tsunami’s backwash it was likely mixed into the earth below.

And yet, Rizaldi very specifically wrote “lost” not “deceased.”

Even seven years later, people in Banda Aceh still whisper about miraculous homecomings, about individuals who were swept out to sea, ended up in Thailand, and had only recently found a way to return. I swatted aside the last branch and found myself staring over the beach, past the pillows of silvery foam at the waterline of the gentle ocean, into the turquoise and glassy reaches beyond.

It had been nearly two months since Rizaldi was “lost.”

As I batted aside branches, I wondered whether Rizaldi’s sister rested here. If her body hadn’t been sucked into the ocean by the tsunami’s backwash it was likely mixed into the earth below.

And yet, Rizaldi very specifically wrote “lost” not “deceased.”

Even seven years later, people in Banda Aceh still whisper about miraculous homecomings, about individuals who were swept out to sea, ended up in Thailand, and had only recently found a way to return. I swatted aside the last branch and found myself staring over the beach, past the pillows of silvery foam at the waterline of the gentle ocean, into the turquoise and glassy reaches beyond.

It had been nearly two months since Rizaldi was “lost.”

~

When I finished reading Rizaldi’s diary for the first time, just as I was about to put it down, I noticed the following words penned on the bottom of the cover: “This turtle is crying… Aceh right now is crying… But look again in thirty years. Look at the back of the book.”

The back cover displayed the same cartoon turtle as the front, though its floppy hat with chinstrap had been removed. The reptile’s mouth gaped in what had once been a yelling laugh, but almost seven years before Rizaldi had drawn rows of boxy teeth into the empty space, making the expression look like a grimace. Written across the turtle’s shell were the words: “Thirty years ago Aceh was crying, but now Aceh is laughing, cheerful, and advanced.”

The back cover displayed the same cartoon turtle as the front, though its floppy hat with chinstrap had been removed. The reptile’s mouth gaped in what had once been a yelling laugh, but almost seven years before Rizaldi had drawn rows of boxy teeth into the empty space, making the expression look like a grimace. Written across the turtle’s shell were the words: “Thirty years ago Aceh was crying, but now Aceh is laughing, cheerful, and advanced.”

~

Note: This article was produced with the support of a Glimpse Fellowship, a travel writing grant partly sponsored by National Geographic.